In exploring the life of the ubiquitous U.S. $1 bill, we delve into not just a piece of currency, but a symbol of everyday commerce and an artifact of economic endurance. Despite being the lowest denomination of paper currency in the United States, the $1 bill plays a pivotal role in numerous transactions across the country. It’s the workhorse of the American economy, frequently used for small purchases, tipping, and change.

Interestingly, the lifespan of a $1 bill is relatively short compared to higher denominations. On average, a $1 bill remains in circulation for about 6.6 years, according to the Federal Reserve. This lifespan is determined by the wear and tear from daily handling, environmental factors, and the physical processes involved in the bill’s life cycle—from printing to eventual shredding.

Understanding the lifespan of this essential component of the U.S. monetary system offers insights into broader topics such as the durability of paper money, economic cycles, and the evolving nature of transactions in an increasingly digital world.

Understanding Money

What is a U.S. $1 Bill?

A U.S. $1 bill is a denomination of American currency featuring the portrait of George Washington, the first President of the United States. It is the most commonly used banknote in everyday transactions across the nation. The bill is also known as a “one dollar note” or simply a “dollar.”

The design of the $1 bill has remained relatively consistent over the years, although security features and aesthetic elements have been updated periodically to prevent counterfeiting and enhance durability. On the front, the bill displays the portrait of George Washington, while the back showcases the Great Seal of the United States, which includes an eagle and a shield.

Produced by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, U.S. $1 bills are made from a blend of cotton and linen, which gives them a distinct texture and durability compared to regular paper. This composition helps the bills withstand the rigors of daily use, although they still have the shortest lifespan among U.S. banknotes due to their frequent handling.

In circulation, the $1 bill plays a crucial role in small-scale financial transactions, such as buying inexpensive items, paying tips, or making changes. Despite the rise of digital payments, the $1 bill remains an integral part of the U.S. monetary system.

The Role of the U.S. $1 Bill

The U.S. $1 bill holds a fundamental role in the daily economic operations and cultural fabric of the United States. Its prevalence and utility in the American monetary system are underscored by several key functions:

1. Facilitating Small Transactions

The $1 bill is crucial for small-scale financial transactions. It is extensively used for purchases where small amounts of money are exchanged, such as at vending machines, convenience stores, and cafes. Its role in facilitating these transactions ensures that cash remains a versatile and accessible payment option for all economic sectors of society.

2. Tipping and Gratuity

In many service industries, tipping remains a standard practice, and the $1 bill is often the denomination of choice due to its convenience. Whether it’s tipping valets, waitstaff, or baristas, the $1 bill supports a culture of gratuity that is deeply ingrained in the U.S. service economy.

3. Use in Charitable Donations

$1 bills are commonly used in charitable giving, especially in situations where donors contribute small amounts. This can be seen in donation boxes at retail counters, street musicians, and fundraising events, where people frequently donate using $1 bills.

4. Financial Inclusion

The $1 bill is a key element in promoting financial inclusion. For individuals without access to banking services or those who prefer cash transactions, $1 bills provide a necessary means for engaging in everyday financial activities. They help ensure that everyone, regardless of their financial status or access to digital payment methods, can participate in the economy.

5. Educational and Numismatic Interest

For collectors and enthusiasts, the $1 bill is an item of numismatic interest. Special editions, misprints, and older series of the bill often hold significant historical and collector value. Additionally, the bill serves an educational purpose, introducing individuals to the concepts of money management and the broader financial system.

6. Emergency and Backup Use

In situations where electronic payment systems fail or are unavailable—such as during power outages or system errors—the $1 bill provides a reliable alternative. Its role as a backup means of payment underscores its importance in maintaining economic stability and consumer confidence.

Overall, the role of the U.S. $1 bill extends beyond mere currency; it is a vital component of the economic machinery and a cultural staple that facilitates small transactions, supports charitable endeavors, and ensures economic inclusivity. Its continued circulation, despite the rise of digital payments, highlights its enduring relevance in American society.

The lifespan of a U.S. $1 Bill

Factors Affecting Lifespan

The lifespan of a U.S. $1 bill is influenced by a variety of factors, primarily related to its physical handling and the environment in which it circulates. On average, a $1 bill remains in active circulation for about 6.6 years, which is significantly shorter compared to higher denominations. Here are some of the primary factors that affect the lifespan of a $1 bill:

1. Physical Wear and Tear

The most direct factor affecting the lifespan of a $1 bill is the physical wear and tear it undergoes during daily transactions. Being the most frequently used denomination for small transactions, $1 bills pass through many hands, machines, and environments, each interaction contributing to its gradual deterioration.

2. Environmental Conditions

Environmental factors such as humidity, heat, dirt, and oils from human hands can degrade the quality of the paper. Bills that circulate in more challenging climates, like tropical or highly urbanized areas with pollution and grime, may have shorter lifespans.

3. Quality of Printing and Material

The quality of the materials used and the printing process itself also play crucial roles. U.S. currency is printed on a blend of cotton and linen, which is more durable than standard paper. However, even this sturdy material can only withstand a limited amount of stress before the fibers begin to break down.

4. Handling Practices

How the bills are handled by individuals and businesses can influence their longevity. Bills kept flat and handled gently will last longer than those that are frequently crumpled, folded, or exposed to chemicals and rough surfaces.

5. Banking and Financial Institution Policies

The policies of banks and other financial institutions regarding the circulation of currency also impact the lifespan of a $1 bill. Banks routinely assess the condition of bills and withdraw those that are deemed too worn for circulation, replacing them with new ones. The efficiency and frequency of these checks can determine how long damaged or worn bills remain active.

6. Technological Advancements in Currency Handling

Improvements in the technology used for handling, sorting, and counting money can extend the lifespan of a $1 bill. Advanced machines that minimize physical stress on the bills during counting and sorting help maintain their condition for a longer period.

7. Cultural and Social Practices

Cultural preferences for cash transactions and the prevalence of cash usage in certain communities or regions can also influence how quickly $1 bills wear out. In areas where cash is less commonly used, individual bills may last longer, simply due to less frequent use.

Understanding these factors is crucial not only for managing the production and circulation of currency but also for planning future innovations in money handling and design that might extend the usable life of paper money like the U.S. $1 bill.

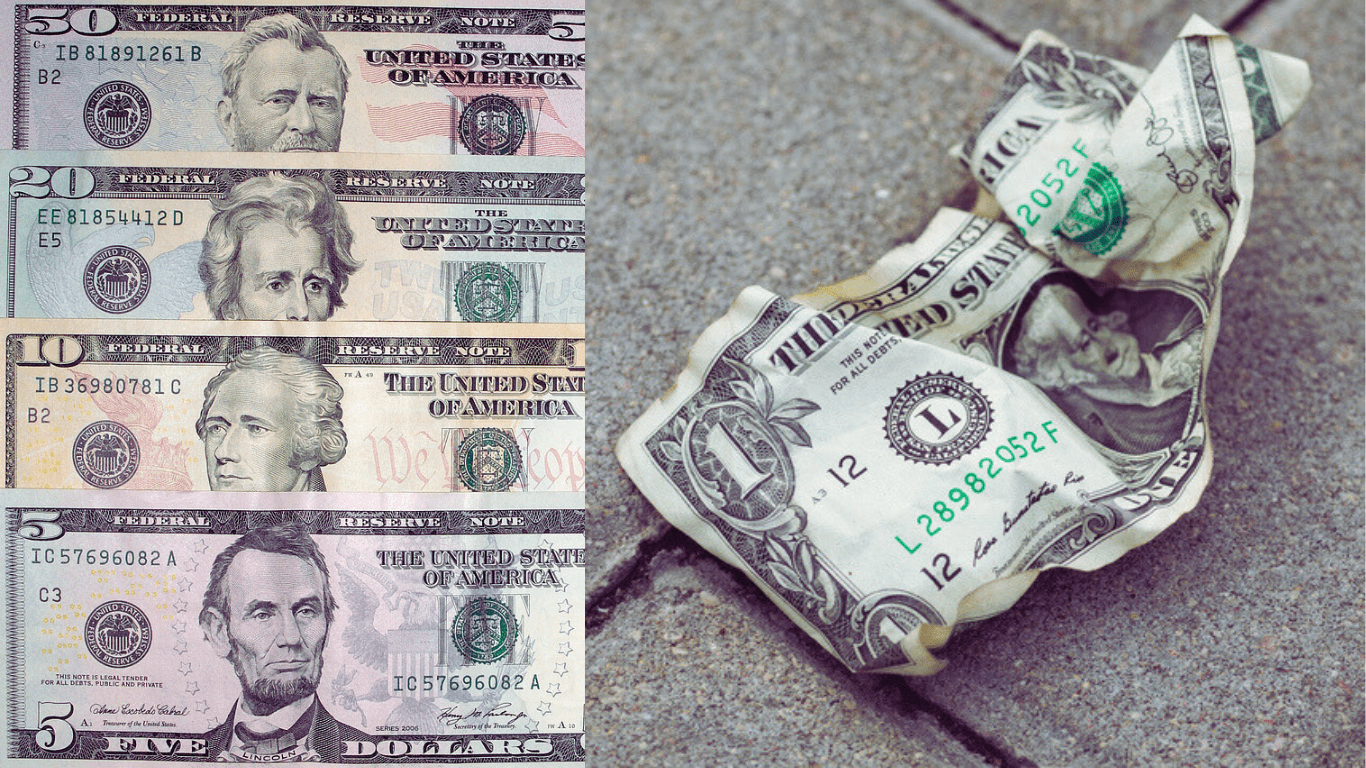

Comparison with Other Denominations

When evaluating the lifespan of a U.S. $1 bill, it’s insightful to compare it with other denominations in circulation. Each bill has a different average lifespan, influenced by its frequency of use, handling, and the roles it plays in the economy. This comparison highlights how the physical and transactional nature of different bills affects their durability and longevity.

1. $5, $10, and $20 Bills

- $5 Bill: The average lifespan of a $5 bill is around 5.5 years, slightly less than that of a $1 bill. This shorter lifespan is partly due to its moderate frequency of use in transactions that are slightly higher in value but less frequent than those involving $1 bills.

- $10 Bill: $10 bills have a similar lifespan to $5 bills, also lasting about 5.5 years. They are used less frequently in daily transactions, which balances their physical wear with their longer retention in wallets and registers.

- $20 Bill: The $20 bill, used often for more significant cash transactions and ATM withdrawals, tends to last about 7.9 years. Its higher value and slightly less frequent use compared to lower denominations mean it undergoes less physical handling per unit of time.

2. $50 and $100 Bills

- $50 Bill: With an average lifespan of approximately 12.2 years, the $50 bill is used less frequently in everyday transactions, leading to its longer lifespan. It is often used for larger purchases or saved for future use, thus experiencing less wear and tear.

- $100 Bill: The $100 bill has the longest lifespan of all U.S. currency, lasting about 22.9 years. Its primary uses include large transactions and savings, significantly reducing its circulation frequency and the associated physical degradation.

Factors Influencing Lifespan Differences:

- Frequency of Use: The most significant factor is how often the bills are used. Lower denominations like $1 and $5 are handled more frequently, leading to quicker deterioration.

- Transaction Value: Higher denominations are generally used for larger transactions, which are less frequent but involve higher stakes, allowing these bills to remain in better condition for a longer period.

- Handling and Storage: Higher denominations are often better cared for; they are more likely to be stored in secure locations like bank vaults or safes, whereas lower denominations are more commonly stuffed into pockets or handled casually.

- Cultural and Regional Practices: In some regions and among certain cultural groups, larger denominations might be preferred for transactions or as gifts, influencing their usage patterns and lifespan.

In summary, the lifespan of U.S. currency varies significantly across different denominations, largely due to differences in how they are used and handled. The $1 bill, despite its vital role in daily transactions, has one of the shortest lifespans due to its extensive circulation and frequent physical handling.

The Production Process

Materials Used

The materials and production process of a U.S. $1 bill are pivotal in determining its lifespan, which averages about 6.6 years. The bill is not made from ordinary paper but from a specialized blend designed to enhance durability and security.

1. Paper Composition

The material used for U.S. $1 bills, and indeed all U.S. paper currency, is a blend of 75% cotton and 25% linen. This combination gives the currency a distinct texture and significantly greater durability than regular paper. The cotton and linen fibers are strong, yet flexible, allowing the bills to withstand folding and bending. Furthermore, tiny red and blue synthetic fibers are randomly distributed throughout the material to add a layer of security.

2. Inks and Printing Techniques

- Inks: The Bureau of Engraving and Printing uses specially formulated inks that are durable and resistant to fading. The ink used for the numbers and some design elements is raised, adding a tactile element that not only helps the visually impaired but also contributes to the bill’s longevity by protecting against wear.

- Printing Techniques: U.S. currency utilizes several advanced printing techniques. The most prominent is intaglio printing, used for the main design elements, including the portrait and numerals. In this process, ink is applied to a plate with recessed areas. The paper is then pressed into these areas under high pressure, which transfers the ink to the paper and creates a raised texture that can be felt. This technique contributes to the durability and security of the bill.

3. Security Features

Although $1 bills do not feature the color-shifting inks, watermarks, or security threads found in higher denominations, the precise engraving and the inclusion of microprinting and serial numbers act as deterrents to counterfeiting and contribute to the overall integrity of the bill during its lifecycle.

The Production Process:

1. Paper Manufacturing

The specialized paper blend is created with cotton and linen, along with the embedded blue and red security fibers. This paper is then supplied to the Bureau of Engraving and Printing.

2. Printing

The first step in printing is the background color and patterns, followed by intaglio printing for the main design features. Each bill is then overprinted with serial numbers and the Treasury and Federal Reserve seals using letterpress printing.

3. Inspection and Cutting

After printing, sheets of bills are inspected for defects. Advanced automated systems examine each sheet to identify any imperfections. Approved sheets move on to be cut into individual bills.

4. Packaging and Distribution

Finally, the bills are gathered into stacks, bundled, and shipped to Federal Reserve Banks, where they enter circulation.

The combination of durable materials and sophisticated printing and inspection techniques ensures that each U.S. $1 bill can withstand years of handling and circulation, fulfilling its role in the economy before being retired and shredded when no longer fit for use.

Withdrawal from Circulation

How Bills Are Withdrawn

The withdrawal of U.S. $1 bills from circulation is a crucial process managed by the Federal Reserve and its associated financial institutions. This process ensures that worn-out, damaged, or otherwise unfit currency is removed from the money supply to maintain the overall quality and integrity of circulating notes.

1. Collection by Banks and Financial Institutions

The process begins when banks and other financial institutions collect currency from daily transactions. As businesses deposit cash and consumers make withdrawals, these institutions serve as the initial filter, separating bills that are visibly worn or damaged.

2. Sending to the Federal Reserve

These collected bills are then bundled and sent to one of the Federal Reserve’s processing centers. Here, they undergo a more rigorous examination to determine their fitness for continued circulation.

3. Automated Processing and Inspection

At Federal Reserve processing centers, bills are processed through high-speed sorting machines. These machines are capable of handling up to 40 notes per second and perform multiple functions:

- Authentication: The machines verify the authenticity of each bill, ensuring that counterfeit notes are removed.

- Fitness Assessment: Using advanced imaging technology and physical sensors, the machines evaluate each bill for signs of excessive wear, tears, stains, and other defects.

- Sorting: Bills that meet the Federal Reserve’s standards for fitness are re-circulated, while those that don’t are marked for shredding.

4. Destruction of Unfit Currency

Unfit bills are shredded. This process might take place at a Federal Reserve bank, or the notes may be transported to a specialized facility depending on the location and the volume of currency being processed. The shredded currency is generally disposed of in an environmentally friendly manner, often being recycled into products like roofing materials or composted if local regulations permit.

5. Recirculation and Replacement

New bills are regularly introduced into circulation to replace those that have been withdrawn. This ensures a steady supply of fresh, clean currency and helps maintain public confidence in the monetary system.

Impact on Currency Lifespan and Quality:

This withdrawal process directly impacts the lifespan of a U.S. $1 bill. By regularly removing worn-out bills and introducing new ones, the Federal Reserve helps ensure that the physical quality of the currency in circulation remains high. This not only aids in the prevention of counterfeiting but also improves the usability and aesthetic appeal of the currency, which is important for consumer confidence.

This systematic cycle of inspection, withdrawal, and replacement is vital for maintaining the robustness and reliability of the U.S. currency system, ensuring that the physical currency remains a viable and trusted medium for transactions.

What Happens to Old Bills

When U.S. $1 bills reach the end of their lifespan—whether due to wear, damage, or soiling—they undergo a systematic process of removal from circulation. The fate of these old bills is carefully managed to ensure both security and environmental responsibility.

1. Shredding

The primary method for disposing of old bills is shredding. This process is carried out in secure environments either on-site at Federal Reserve banks or at designated shredding facilities. The shredding process ensures that the decommissioned bills are destroyed, preventing any possibility of them re-entering circulation or being misused.

2. Recycling

Once shredded, the remnants of the old bills often find new life through recycling. The material from shredded currency can be repurposed for various uses, such as:

- Manufacturing Paper Products: Shredded bills can be mixed with other types of paper to create recycled paper products.

- Compost and Mulch: In some cases, the shredded material is processed into compost or mulch, which can be used in agricultural or landscaping applications.

- Industrial Materials: Some innovative uses include incorporating shredded currency into building materials like roofing tiles or incorporated into everyday items like pens or coasters.

3. Novelty Items

In certain instances, shredded currency is packaged and sold as novelty items. These packages, often clear plastic bags or embedded in items like paperweights, are popular as educational tools or unique gifts, giving a second, albeit non-monetary, life to what was once circulating currency.

4. Energy Recovery

Another disposal method involves using shredded currency as an energy source. The combustion of currency in waste-to-energy facilities helps generate heat and electricity while ensuring the material is completely destroyed, maintaining security.

Environmental and Security Considerations:

- Environmental Impact: The Federal Reserve and associated institutions strive to handle old currency in environmentally friendly ways. Recycling and using shredded currency for energy recovery are part of these efforts, reducing the environmental footprint of the currency lifecycle.

- Security Measures: Throughout the disposal process, strict measures are in place to ensure that there is no risk of old currency re-entering circulation. This includes careful handling, secure transport, and controlled access to shredding facilities.

The treatment of old U.S. $1 bills highlights a commitment to sustainability and security within the monetary system, ensuring that even at the end of their physical use, these bills are disposed of responsibly and innovatively.

Alternatives and Future Trends

Digital Payments

In recent years, the rise of digital payments has significantly impacted how transactions are conducted globally, offering convenient alternatives to cash and potentially altering the future demand for physical currency like the U.S. $1 bill.

1. Current Alternatives to Cash

- Credit and Debit Cards: These remain among the most common alternatives to cash. They are widely accepted for both online and in-person transactions.

- Mobile Payments: Services like Apple Pay, Google Wallet, and Samsung Pay allow users to store card information on their devices and make contactless payments using near-field communication (NFC) technology.

- Online Payment Platforms: PayPal, Venmo, and similar platforms facilitate easy transfers and payments directly between users or at online retailers.

- Cryptocurrencies: Although more volatile and less widely accepted than traditional payment methods, cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin and Ethereum offer a decentralized alternative that some users find appealing.

2. Future Trends in Digital Payments

- Increased Use of Contactless Payments: The convenience and speed of contactless payments are driving their increased adoption. This trend was accelerated by health concerns due to the COVID-19 pandemic, pushing more retailers to adopt and promote contactless payment technologies.

- Greater Financial Inclusion: Digital payment platforms are expanding access to financial services, especially in underbanked regions. Mobile money solutions in places like Africa (e.g., M-Pesa in Kenya) are prime examples of how digital finance can revolutionize economic participation.

- Regulation and Security Enhancements: As digital payments grow, so too does the focus on improving their security. This includes enhanced encryption, biometric security measures, and regulations that protect users from fraud and theft.

- Integration of AI and Machine Learning: These technologies are being increasingly utilized to detect fraudulent activities in real-time and personalize the consumer experience, making digital transactions both safer and more user-friendly.

- Rise of Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs): Several countries are exploring or have already implemented digital versions of their national currencies. These digital currencies aim to combine the convenience and security of digital forms with the regulated, reserve-backed money circulation of traditional banking.

Implications for Physical Currency

While digital payments offer numerous advantages, they also pose challenges to the future relevance of physical currency. The convenience, security, and potentially lower costs of digital transactions could decrease the demand for cash. However, cash continues to hold significant importance due to its reliability during digital system failures, its universality as a form of payment, and its anonymity.

The balance between digital payments and physical currency will likely continue to evolve, influenced by technological advancements, consumer preferences, and economic policies. While it’s uncertain how quickly digital payments will supplant cash, the trend towards digitalization in financial transactions is clear and will profoundly impact monetary systems worldwide.

Conclusion

The estimated lifespan of a U.S. $1 bill, generally around 6.6 years, reflects its role and utility in the modern economy, balancing between traditional uses and the rise of digital alternatives.

Read also: What is InMail on LinkedIn?